Rebuilding our Research Foundations

Happy Monday! Today, I look at Canada’s research landscape amid an unprecedented moment. Decades of underfunding, coupled with an underappreciated global decline in research productivity, have left us ill-prepared to take advantage of the research exodus from the United States. If we aren’t going to waste a golden opportunity, we need to look beyond policies to attract research and turn to addressing the systemic weaknesses and underfunding of our research system.

The Challenging Research Landscape

Photo by ThisisEngineering on Unsplash

Canada’s stagnant research funding is a matter of frequent debate, yet the underlying decline in research productivity and its implications is not often considered.

Most often, this focuses on the human costs. Recent research has found that “stipends for biology and physics graduate students at Canadian universities fall well short of a living wage.” The authors estimate that stipends would need to increase by 1.5 times to merely keep pace with the cost of living, while surveys from the Canadian Federation of Students’ National Graduate Caucus have found that 70% of graduate students are living below the poverty line. Not only have these low levels of funding exerted a ridiculous human toll on those who have suffered, but they have also driven promising research abroad to find opportunities.

Furthermore, these low funding levels have hurt Canada’s competitiveness. The Bouchard Report made this abundantly clear, stating plainly that:

To put it starkly, current support for graduate students—the researchers of tomorrow—is at a breaking point. The values of the government's awards for university research trainees have remained virtually stagnant for the past 20 years. As a result, they have not kept pace with increases to the cost of living nor with research trainee compensation trends around the world—a situation that significantly dampens Canada's position as a global hub for the attraction and retention of research-enabled talent. Recent analyses show that the award levels offered by Canada's federal scholarship and fellowship programs result in a lower material standard of living for our graduate students and postdoctoral fellows than those available in comparable countries.

Budget 2024 went some way to address this, with a $825 million allocation towards scholarships and fellowships. However, even these higher awards still lead some students below the poverty line and only left Canada in the middle of the pack among comparable countries for graduate support. Furthermore, the lack of indexing stipends to inflation means that these new amounts will quickly erode in actual purchasing power, leading, once again, to ever more researchers being stuck below the poverty line.

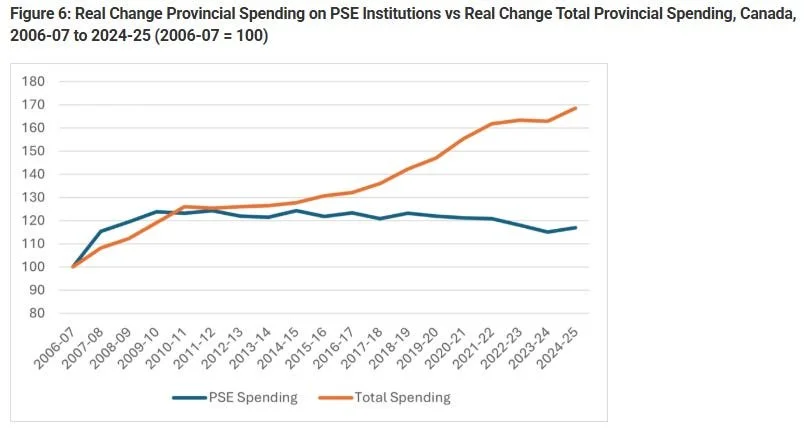

This is not the only way we have been underfunding research. Alex Usher has frequently written about how we are “eating the future” by failing to invest in postsecondary education and research. Amid massive increases in total government spending by the provinces (30% over and above inflation over the last decade), support for postsecondary institutions is actually down 30% as a portion of total spending.

Source: Alex Usher, “More Eating the Future”, Higher Education Strategy Associates, 2025-01-06, https://higheredstrategy.com/more-eating-the-future/

As Usher concludes, given this drop's universality across the Provinces, “none of them think PSE is worth greater investment.”

These are challenging circumstances for the Canadian research enterprise. Yet, the decline in research productivity further exacerbates them — something we don’t consider enough.

Research Is Getting More Difficult

The root of the research productivity challenge is quite simple. To move the research frontier forward, you need to be on top of what has come before you. Yet, every year, vast new amounts of research are produced, and it takes longer and more resources to catch up with what has come before.

A wide range of metrics and evidence point to how this is happening and how it is ever more difficult to make discoveries that are as impactful as ones in the past. Matt Clancy’s invaluable New Things Under the Sun living literature review on the research about innovation is helpful for mapping these out.His piece on this sets out the evidence of how:

The share of citations to recent academic work by other papers and by patents has been falling significantly over decades, indicating that newer work isn’t as transformative or foundational as older research

New papers have a smaller chance of becoming a top cited paper or winning a Nobel prize within twenty years: “Prior to the 1970s, on average 90% of the time, awards went to papers published in the last twenty years. But by 2015, the ten-year moving average was closer to 50%.”

The number of new topics studied is stagnating, with fields remaining stuck on the same things (i.e we’re seeing less moving from electrons to quarks to strings and more strings to strings to strings)

New patents are citing recent papers less.

Similar trends are impacting innovation as well as scientific research. A landmark paper by Nicholas Bloom, Charles I. Jones, John Van Reenen, and Michael Webb measured the productivity of researchers and the rate of innovation across a wide range of innovation case studies and data sets, such as semiconductor innovation, agricultural yields and health outcomes. They concluded:

Our robust finding is that research productivity is falling sharply everywhere we look. Taking the US aggregate number as representative, research productivity falls in half every 13 years: ideas are getting harder and harder to find. Put differently, just to sustain constant growth in GDP per person, the United States must double the amount of research effort every 13 years to offset the increased difficulty of finding new ideas.

Furthermore, they found that “research productivity for the aggregate US economy has declined by a factor of 41 since the 1930s, an average decrease of more than 5 percent per year.”

One easy way to see how this plays out is with Moore’s law—the idea that the number of transistors on a computer chip doubles every two years. This law has held up for decades now, but maintaining that rate of progress has required vastly more resources. Bloom and co-authors found that it takes twice as many researchers every 14 years to maintain that pace, with research productivity declining by 7% per year. The result is that it takes 18 times more researchers to double chip density today than in the early 1970s.

We can also see this play out in how multinational firms increasingly offshore R&D in the same way they used to offshore production and manufacturing. Research from Lee Branstetter, Britta Glennon and J. Bradford Jensen has found that the increasing globalization of R&D has been driven, in particular, by the need for MNEs to access a global talent base to “support a high rate of innovation even in the presence of the rising (human) resource cost of frontier R&D.”

Artificial Intelligence may alter this picture in time. Advances like AlphaFold clearly demonstrate its potential to rapidly increase research productivity. However, we can’t ignore that AI itself requires vast resources. These include the costs of hiring armies of talented researchers and the need to account for huge infrastructure and environmental costs. Even if AI is able to increase the productivity of researchers, ever more resources will still be needed.

Canada and Declining Research Productivity

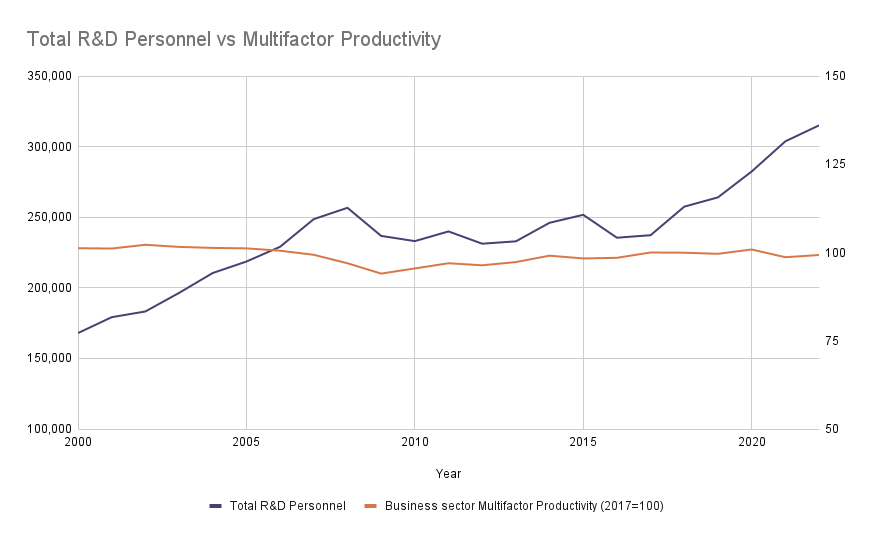

Turning back to Canada, we can see how declining research productivity is impacting us. While federal research funding has been stagnant for a long time and provincial post-secondary funding is declining, we are nonetheless dedicating much more to research and development than in the past.

Since 2000, total expenditures on R&D have increased by 163%, from $20.5 billion to $54 billion as of 2024 (current prices). Federal funding for R&D has also increased 150%, from $3.5 billion to $8.8 billion. We have also seen an 87.5% increase in R&D personnel since 2000. Yet, none of this has resulted in increased multifactor productivity for Canada:

Source: Statistics Canada Table: 27-10-0023-01 and Table: 36-10-0208-01

These increases in resources, where they have occurred, simply aren’t enough to counter reducing research productivity. And that is ignoring wider weaknesses in our innovation ecosystem that impact multifactor productivity, such as our commercialization and technology adoption challenges.

Let’s look at NSERC’s funding for research as an example of the research funding gap. If we assume that research productivity falls in half every 13 years, then to maintain the 2011 levels of research productivity, NSERC’s funding would have needed to be $2.75 billion, taking inflation into account (which, as we’ve explored, isn’t what happens usually). Unfortunately, NSERC’s 2023-24 funding wasn’t even half that, coming in just below at $1.357 billion.

Combined with declining provincial funding for post-secondary institutions and the general disregard for the well-being of our graduate and postgraduate researchers, Canada’s baseline is a country going backwards when it comes to research outcomes, not forward.

Taking Advantage of a Research Opportunity?

All of this is a pretty damning picture and one that leaves us unable to take advantage of the current moment. It should be astoundingly clear that the research enterprise in the United States is under an unprecedented authoritarian assault. As Christina Pagel has wrote:

Foreign scientists in the US are scared to publish anything perceived as critical for fear of being bundled off the street to a detention centre. Foreign scientists abroad are scared to go to the US because they have voiced criticism of the state. The US is actively cracking down on perceived dissenters and foreigners are the most vulnerable to arbitrary detention and lack of due legal process. The vaunted first amendment guaranteeing free speech has become a bitter and twisted joke.

This is in addition to massive job cuts and revoked grants that are hitting researchers. The result is a potential exodus of talent. When Nature polled 1,600 researchers, 75% of them said they were considering leaving the United States, with many looking to Canada.

Unsurprisingly, there have been plenty of calls for Canada to take advantage of this. After decades of underinvestment and Canadian brain drain, this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to attract some of the brightest minds in the world.

We should pursue this. While that underinvestment has left us without much excess capacity that can suddenly absorb and fund that talent, there are plenty of ideas out there of the levers to pull to take advantage, such as using provincial tools such as the Ontario Research Fund, expanding the Canada Research Chairs program and providing new funding to transfer US researchers work and labs to Canada, or turning to philanthropy to fill the gaps government won’t.

These are all valuable ideas. However, we need to be clear that landing a handful of headline researchers will not be enough on its own to reverse the long-term decline in research productivity or fix our wider productivity challenges. If we really have ambitions to strengthen our sovereign capacities, then we need an investment in research that is a whole order of magnitude larger and more ambitious. It also needs to take a holistic view of the other weaknesses in our current system that prevent the fruits of research from being felt, such as procurement and IP policy, as Kyle Briggs has examined.

We’re at a critical juncture. The convergence of stagnant funding, declining research productivity, and a global talent shift demands immediate and decisive action. To capitalize on the opportunities ahead of us, as well as mitigate the threats we face, we need a transformative vision for research that substantially increases funding and takes into account existing systemic weaknesses. One thing is for sure, though: the path of inaction is a path of decline, one that will leave us ill-equipped to face the complexities of tomorrow. It’s time for a long-term vision that positions Canada, once again, as a global leader in research and innovation.